I visited Esperanto House: Now I know world peace

Headquarters, lodging, and museum all hide modestly on the Redfern Run. Dressed in camouflage, they escape the ocular frisk of students rushing to Abercrombie.

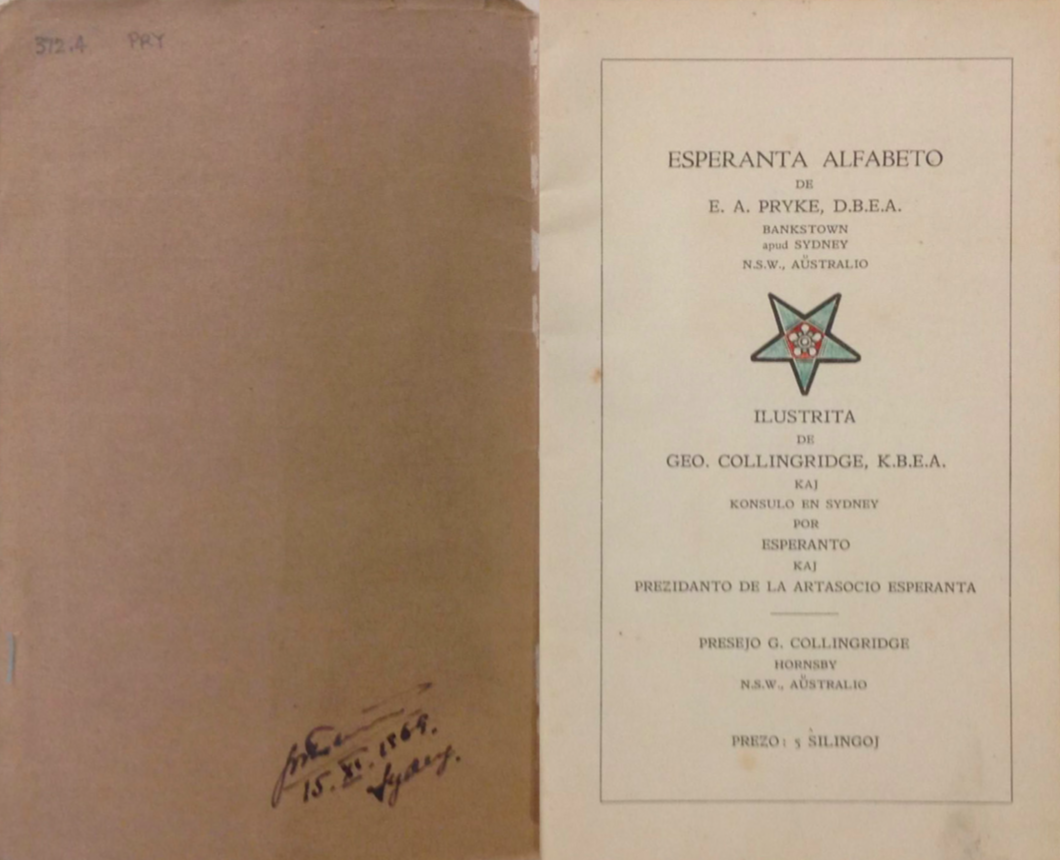

Image Credit: Australian Esperanto Association

Students whose feet have trampled the run for years are unaware of its invisible presence at 143 Lawson Street. The modest brick front and below-eye-level steel sign belie the complicated myth flourishing inside its walls.

“Have you heard of the Esperanto House?”, I ask my friends, walking sideways like a crab in order to squeeze four abreast onto the Lawson Street capillary.

Furrowed brows. Shaken heads.

By some synchromystic event, we happen upon the storied institution seconds later.

A chorus of “I never noticed it!” sings out.

*******

Once you’ve been alerted to the Esperanto House’s existence, like I was in first year, it demands your glued gaze every time you pass by in future. After many university journeys of passive intrigue, I decided I ought pay its interior an overdue visit.

Sodden from a Wednesday afternoon downpour, I wrung out the fringes of my denim jacket at the front doorstep. My feet rhythmically shuffled on the doormat, dislodging the leaf litter curled in the ridges of the sole.

I stepped into a linguist’s paracosm, where each coconut-flesh wall shone. The spotless surfaces were adorned with flag-green posters championing Esperanto’s history, forebears, and key linguistic elements. On the right hand side lay a flood of sleek Monato magazines, a monthly Esperanto publication printed in Belgium.

Dmitry Lushnikov, board member of Esperanto NSW, rolled out the welcome mat despite my spontaneous Wednesday walk-in. He first asked me if I knew much about Esperanto — a man-made, basic language aiming to engender world peace. Creator Ludovik Lazarus Zamenhof spearheaded both the language’s construction and an accompanying social movement, as he sought to synthesise harmony by creating an easy-to-learn second language. Zamenhof was a dreamer, his body limping behind the sprinting passions of his mind. A precocious innovator, he handed out favours of a proto-Esperanto dictionary at his 19th birthday party.

He is immortalised by a miniature statue that greets guests on the front desk.

We then snaked through a forest of green-laden rooms. Behind the front room is a cosy teaching area with whiteboards — Lushnikov explained that they hold classes of all levels there.

Behind the classroom hid a more startling sight. Lushnikov opened the door to reveal a basic yet inviting lodging room. To the seasoned Esperantist traveller, this is not surprising — at all Esperanto Houses worldwide, language-speakers can reside there for up to two weeks for no cost. The only price is a knowledge of and passion for Esperanto — sign me up for this unconventional summer sub-let! Lushnikov told me that, as imagined, the bedding collected dust during COVID-19’s peak, but is now frequented by a flux of interstate and international tourists. Typically, renters are expected to be Esperanto speakers, or study Esperanto one hour a day for the duration of their stay. However, this stipulation was waived for two Ukrainian patrons in September 2022, “as they have experienced many difficulties during the war in Ukraine.”

We climbed the stairs of the main building and Lushnikov revealed a planetarium of wonders; chessboards sat squarely like suns in the middle of the room, and we orbited around them. I learned that the House is also home to a chess club for Esperantists on Wednesday nights. If prose tickles your mind more than logic, the Wednesday evening book club may be more your stead. Peckish language-learners can also attend nights of gastronomic delight, such as “Bagel night”.

Many might question why the Board is willing to provide such amenities and activities for little to no cost. To the ardent Esperantist, learning the language is more than mastering grammatical sub-units. Esperanto encompasses inter-cultural exchange and communication; Lushnikov told me, “These facilities are offered for free because we believe that Esperanto, like any language, is only as strong as its community of speakers, and that there should be no barrier to anyone with a sincere desire to learn it.”

Excitingly, Esperanto House might undergo a facelift in the new year. Lushnikov revealed the Board’s plans to build a cafe facing passerbys, selling coffees to sleepy students. During the Board’s AGM, they entertained other ideas to promote Esperanto, such as buying a block of land and constructing an ‘Esperanto Village’, or hiring a campervan and decking it in Esperantist paraphernalia.

Unsupported by generational institutions, champions of Esperanto face some difficulties with funding to promote the culture — as Lushnikov put it, “Many national governments financially support their own national languages. However, because Esperantois a language that belongs to no-one (or rather, everyone), not-for-profit organisations such as ours must ‘fill the gap’.”

Esperanto has faced myriad criticisms which have prevented its uptake by a greater population, such as its Eurocentric linguistic composition. Cognisant of its flaws, but believing more in its benefits, the Esperanto House nurses the flame of hope that the language’s popularity may mushroom. Modern-day Esperantists are filled with salt-pillared yearning, never forgetting Zamenhof and his dream for a better world.