Saigon Surf: a genre lost & found

Nothing is ever truly final, and much like music, is forever-changing again and again

Image Credit: Bandcamp

Vietnamese music laments, it does not howl. I first discovered Phương Tâm’s body of work through the Spotify algorithm. Raucous and dry as much as it’s cheerful. Her voice roared through statics and crackles of the old remastered work.

‘Nhịp Đàn Vui (A Merry Tune)’ begins with a gleeful chorus countdown. Then, thunders down something unlike any voice I’d heard before:

Ca lên cho vui

Mừng ngày tự gio đã đến đây rồi

Sing to be happy

Celebrate freedom that’s arrived

Viet singers of the 60s (and even now) exhibit a clear and sweet singing style. Tâm is different. At just 19, her voice was as raspy as a 50-year-old smoker’s. Instead of being refined, she wasn’t afraid to scream.

But more than this, it is the difference in the music that mystifies me. This song is incomparable to other 1960s Saigon genres, such as boleró or traditional music. Rather, it is an infusion of American surf rock, jazz and blues, glossed over in Vietnamese lyrics. It is dirty, emotive, and unapologetically cheerful.

Later on, I found out that this is called ‘nhạc kích động’ or ‘action music’, a belting genre with American rock ‘n’ roll influences.

“Back then, it was only me who was singing that genre of music,” Tâm told me through a glitchy WhatsApp call, sitting next to her daughter in San José. “And the sad thing is, for over 50 years, everything was lost.”

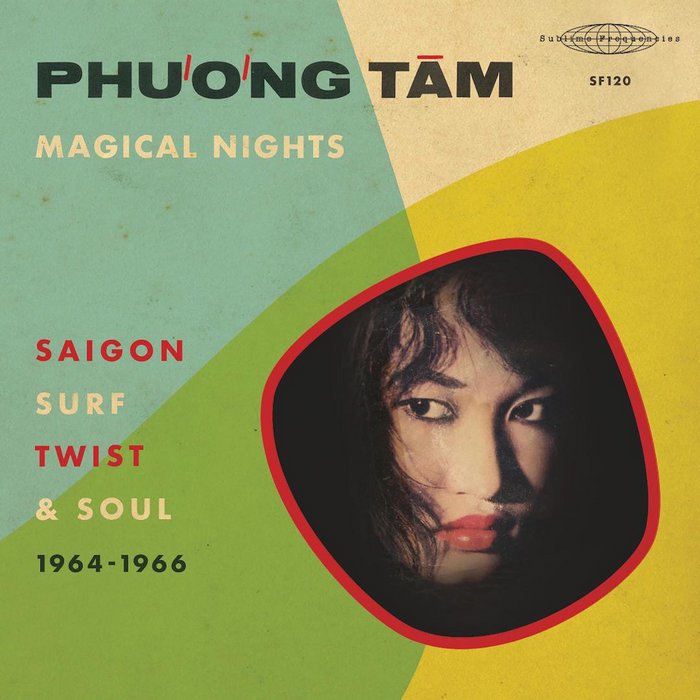

Magical Nights — Saigon Surf, Twist & Soul (1964-1966) is Phương Tâm’s first-ever retrospective album. Its 2021 release can thank the dedicated efforts of Tâm’s daughter Hannah Hà and music producer Mark Gergis. They restored the lost recordings of Tâm’s work, essentially bringing back a missing puzzle in Vietnamese music history.

The early 1960s saw American music influencing Vietnamese tastes. Previously enamoured by folk opera, French jazz and boleró, the younger generation became more fascinated by cultural artefacts brought over by American G.I.s In Saigon, radio waves and nightclubs took over with the likes of The Ventures to The Rolling Stones. It was the birth of a vibrant Vietnamese rock scene in which Tâm was the centrepiece.

She always wore an áo dài when performing, the national dress often associated with Vietnamese schoolgirl femininity. When I asked why, she laughed, “I love wearing áo dài. When I’m out and about I would wear Western dresses, but when performing, always áo dài. Nguyễn Ánh 9, a fellow artist, once told me ‘You sing rock n’ roll, you should wear shift dresses and mini shorts.’ But I liked áo dài!”

Vietnamese writer Mai Thảo wrote about the áo dài’s presence in 1962: "As she steps from the back and moves toward the microphone with glittering eyes her hands clapping to the beat — a new shape emerges. The figure is now drawn with burning flames, like a green fruit ripening before your eyes.”

Nhạc kích động was then borne from the South Vietnamese government’s prohibitions on the distribution of Western music. “You could perform songs in English, but you couldn’t record them. This ultimately led composers to record rock’n’roll in Vietnamese. Cause then, it was no longer purely ‘American’ music.”

It was these recordings that then became Magical Nights. Tâm was the only singer doing it, and what emerged was a new genre.

With the fall of Saigon in 1975, Tâm’s family evacuated on a cargo plane and arrived in California. Her focus turned to rebuilding a new life: “I had no photos, no recordings. Nothing was kept.”

“When you leave in time of war and you’ve left parts of yourself behind, there’s no other option but to look to the future,” said Hannah, “she never looked back, and much of her music career was forgotten.”

Hannah first discovered that her mother was a musician in 2019. What followed was a driven desire to restore, verify, and distribute the work. She sought out music producer Mark Gergis, who had produced the compilation album Saigon Rock & Soul in 2010. Funnily enough, it was the same album that wrongly attributed a rendition of a song sung by Connie Kim to Phương Tâm, who sang the original track.

“It was a difficult and long process that took a lot of investigation and talking to people,” Hannah described, “we did not know how many songs were recorded and where to even find it. I mean, where do you even find Vietnamese records? You can’t just go to a library.”

“I had to verify whether mom’s records were original recordings. I had to go all over the world to ask collectors and music historians. People who have done 20 years of research.”

“And you know what’s so interesting? They didn’t even know that she was alive. They were like “She’s alive? Living in Central Bay?”. They didn’t even know what she looked like”, she laughed. “It was a history lost to even its own artists.”

Over two years, they sought out collaborators from all over the world. From “Germany, Australia, England, Vietnam.” Hannah described this as a process of “extracting history” through exchanges that would slowly piece together the truth.

As we approached the end of the call, it came to me how we were three generations of Vietnamese people, all in the process of rediscovering our own roots.

The composer Y Vũ, who wrote ‘Đêm Hyuền Diệu (Magical Nights)’ upon listening to Tâm’s original recording of the song exclaimed “I’d found love again.” And Tâm had cried when she first listened to the record.

From tearooms to Spotify, Magical Nights have opened up new possibilities of how we view and reflect upon predominant narratives about Vietnam. It’s reminded us that nothing is ever truly final, and much like music, is forever-changing again and again.

Có nhớ đêm nào?

Nhìn chung ánh trăng mơ màng

Hạnh phúc tìm đến đây rồi

Ðời là một bài thơ

Remember that night?

We stared together at the dreamy moonlight

Happiness has found us

Life is a poem