The mythology of Soong Meiling

Let’s gossip, spread some rumours, and theorise imaginatively.

Image Credit: National Institute for Defense Studies, Tokyo & Shangahi Library

As a child, I often felt ‘too white’ for the “real” Chinese kids and ‘too Asian’ for the white kids. I felt uneasy, afraid of disappointing my parents for not being Chinese enough (don’t tell them I preferred Kim Possible over Dragon King). All of these insecurities would dissipate at the dinner table, when my grandparents shared stories of Chinese historical figures: tales of heroic deeds (Yue Fei) and nefarious acts (Wang Jingwei), of ancient legends (Yu the Great) and modern-day radicals (Lu Xun). But I always felt bizarrely allured by one story in particular — that of 宋美龄 (Soong Meiling) — the second First Lady of China.

I remember hearing stories about Meiling long before I knew who her husband Chiang Kai-shek was, before I even understood the concept of Republican China. In my mind, she was an intelligent, US-educated, young woman whose ambition and drive propelled her to become one of modern China’s most influential figures. Born into a powerful web of political intrigue: her father was rumoured to be involved with Shanghai’s burgeoning criminal underworld, her eldest sister married a wealthy industrialist who later financed the Kuomintang (KMT, the party to which Chiang Kai-shek belonged), and her middle sister married Sun Yat-sen, the first leader of the KMT and ‘father’ of modern China.

Despite her importance in Chinese history, there is a lack of authoritative writing on Meiling, except for Emily Hahn’s Soong Sisters (1941) or Jung Chang’s Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister (2019). So inevitably, I delved into the murky oeuvre of internet writing on Meiling’s legacy:

Madame Chiang Kai-shek singlehandedly “charmed” the US into supporting Republican China in the Civil War. She dreamt of global domination and rule, even if it meant seducing a potential American president at the behest of her husband.

Foreign journalists, often American and British, have traditionally depicted Meiling as a hyper-sexualised, power-hungry Dragon Lady. (Maybe her Philosophy professors at Wellesley taught her the art of political seduction.) Oftentimes, they exclusively wrote about her encapsulating beauty and figure-hugging qipaos rather than her numerous other accomplishments, as if following a standardised template titled ‘Sexy Oriental Wife’.

For a woman described as one of the architects of modern China, Meiling’s legacy is shrouded in mystery. Maybe the best way to learn about her then, is to feed into the gossip…

妈妈,你对宋美龄的印象是什么?Mum, what do you think of Soong Meiling?

Growing up in 1970s China, my mother was taught a similarly simplistic narrative: Meiling loved power. As Mao’s infamous saying goes: “One loved money, one loved power, one loved her country.” Leading a life of luxury and opulence, it was said that Meiling even bathed in fresh milk, as beauty remained a paramount concern well into old age.

Like many foreign journalists at the time, my mother quickly realised that her younger self underestimated Meiling’s political prowess. She told me about how during the Xi’an Incident, Meiling personally engaged in negotiations with Zhang Xueliang, securing the release of Chiang Kai-shek after he was kidnapped in 1936. Meiling also travelled around the US, working tirelessly to promote China’s war efforts against the Japanese.

After a long conversation, my mother said: “宋美龄的人意很好” (Meiling was a good person). She used the word ‘人意’, for there is no adequate English translation. 人意 is a rather ambiguous term, but largely refers to one’s morals, values, and capacity to empathise with others.

婆婆,你对宋美龄的印象是什么?Grandma, what do you think of Soong Meiling?

“宋美龄很能干!” My grandmother proclaimed immediately: Meiling was very capable. And indeed she was. Having graduated from the prestigious Wellesley College, Meiling’s higher education was a rare feat for women of her time. Fluent in English and at least four other languages, she was the perfect interpreter, capable of navigating the perilous waters of wartime diplomacy.

In many ways, Meiling was the ‘political mastermind’ behind Chiang Kai-shek, the ‘Jackie Kennedy’ of modern China if you will. But like many Chinese grandmothers, mine believed that Meiling’s successes in diplomacy were attributed to her beauty. Even over WeChat, my grandfather’s fervent dissent was palpable, his strong expressions of the contrary lingering in the background for the remainder of our call.

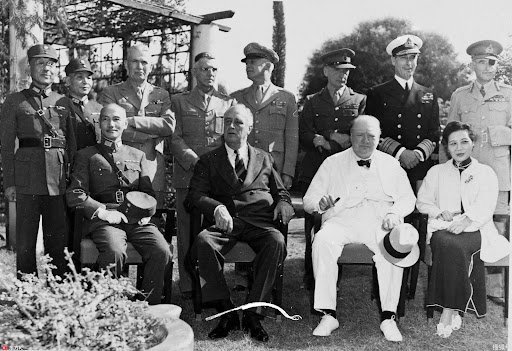

Soong Meiling attending the 1943 Cairo Conference as her husband’s interpreter. Pictured from left to right is: Chiang Kai-shek, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soong Meiling. Courtesy of Hoover Institution Archives.

Soong Meiling attending the 1943 Cairo Conference as her husband’s interpreter. Pictured from left to right is: Chiang Kai-shek, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soong Meiling. Courtesy of Hoover Institution Archives.

Soong Meiling was undoubtedly a product of incredible privilege, having been given countless opportunities reserved only for Shanghai’s elite socialites. This is perhaps one of the few statements I can unequivocally claim about Meiling. But was she a power-hungry woman who intended to manipulate Wendell Wilkie? I suspect if journalists of the 1940s paid closer attention to the content of her speech rather than the length of her dress, they would’ve been closer to uncovering this question.

Amidst the uncertainty, I yearn for more factual histories to be published on Meiling. It is difficult to imagine 20th-century China without her, but documentation which acknowledges her significance in history is scarce. In the meantime, all we can do is attempt to fill the gaps. Let’s gossip, spread some rumours, and theorise imaginatively: 宋美龄到底是谁? Who was Soong Meiling?