Mirrors

I sit cross-legged before the mirror yet again. What do I see? I see a face. Is it me, or some Other?”

All image credits: Alexa Hansen-Weeks

I look into the mirror once more. I might be able to say with conviction that that is who I am, that is me.

Entry one: Identity is housed in memory.

I am twelve, walking along Richmond’s riverbank, and I pass the plaque of Woolf’s home:

“If it is a choice between Richmond and death, I choose death.” I am twenty-two now, looking down over The Gap’s precipice. Were it not so beautiful, the whole experience would be unnerving. I hike past the watchful eyes of security cameras; dissuading signs bore into me.

I close my eyes. The images my mind conjures up are frightening; the immersion of the self, the dissolution of the self, the water lapping hungrily below. Strange, I think, how two places so far from one another can evoke such similar sentiments.

I feel a kind of homesickness wash over me at once, a burning desire to go home. I think of Shaun Tan, who captures this feeling so astutely throughout his story No Other Place. Its plot is centred around the discovery of a courtyard, one that encapsulates the qualities of its struggling inhabitants’ home country, providing them with a place of refuge and isolation from the monotony and unfamiliarity of Australian suburbia. Tan presents the story within an undeniably whimsical framework: the accompanying art is reminiscent of fantasy novels or children’s picture books, the prose lyrical, the plot’s continuous suspension of disbelief recementing the courtyard as a strange and fictitious place akin to C.S Lewis’ Wardrobe or Alice’s Looking Glass.”

Certainly, the family feels “no need to question the logic of it,” simply because its presence seems to have successfully disrupted the geo-physical and psycho-social boundaries imposed by the hostile world beyond it. And yet, by the story’s end, a neighbour corroborates that the setting is a widespread feature of Australian homes: “Yes, yes, every house here has the inner courtyard, if you can find it…nowhere else has this thing. No other country.” In his affirmation of the courtyard’s existence, Tan’s neighbourly character does not collapse the story’s fantasy. Rather, he seems to suggest that the courtyard is indicative of a shared cultural propensity for immigrants to look inwardly to ratify our identities, to compare ourselves to our ethnic predecessors. No Other Place’s story pedals a narrative that is an undeniable celebration of Australia’s modern-day multiculturalism; its allegorical safe haven suggestive of our country’s supposed capacity to reaffirm the hereditary of its expatriates whilst they endure on foreign land.

Will I find my ‘inner courtyard’ here? I look out at the water now, but I feel no sanctity in it, no comfort in its swirling depths. Was moving to Watson’s Bay some great mistake, the result of mismanagement? I tell people I am an expatriate, but I don’t say it with much conviction. The word itself is ugly. ‘Ex’ as in was, Latin connoting that I am without something.

Home is like a phantom limb; the body’s memory of what is lost.

I suppose the problem of identity is felt more acutely by some more than others. Christina Stead’s novel, Seven Poor Men of Sydney raises such metaphysical concerns in its characterisation and portrayal of Michael Baguenault, for instance. From its opening few chapters, the Baguenault’s heredity is defined by its indistinctiveness. Whilst their surname is French in its etymological roots, the family is described as having settled in Australia from Ireland “thirty years before.” The conflation of these various cultures with the unsound origin of his predecessors marks the first of many cognitive dissonances that arise within Michael over the course of the novel. The title of the book, its content page abridging the plot, its commentaries on heritage. Stead cements Michael’s character as a victim in something akin to a Greek Tragedy or Christian parable. Readers are forewarned through structure and prelude that some fatalistic message will unravel further as the plot progresses, a sentiment echoed by Joseph’s character later on as he reflects on his cousin’s fate: “I think he was bound to commit suicide.”

I look down at my feet as I walk, a force of habit. How many feet have stood here? The Gadigal land I stand on here is stolen, people have been displaced since long ago. There is a dark history here, one of cultural erasure, of identity and home forever lost.

Kol Blount’s in memoriam for Michael posits a rhetorical question at its very end:

“And after all this notable pioneer tale of starvation, sorrow, escapades, mutiny, death…the sad-eyed youth sits glumly in a harebrained band, and speculates upon the suicide of youth, the despare of the heir of yellow heavy-headed acres. What a history is that; what an enigma is that?”

As in fables or in epic poems, which Stead’s prose draws upon, there is a message to be learned. A person cannot be woven into a cultural matrix within which they do not belong. Around fifty people jump from here each year. There is some epidemiological need for self-destruction inherent within us, perhaps because we want so deeply to belong, but we do not know how we might begin to project ourselves onto the complex social framework that is presented before us.

Michael’s suicide is the ultimate rejection of conformity, paradoxically reaffirming his autonomy and identity. His death is predetermined, it has narratological significance, it creates purpose where there is none. “It is done; all through the early morning the strings of the giant mast cry out a melody, in triumph over the spirit lost.”

Michael Baugenault. His name lives on in Blount’s in memoriam, as a witness and mouthpiece to the creation of the earth. One might also argue that he is immortalised through Stead’s writing itself. It seems wrong to think of fictional characters at a place such as this. People are not usually so fortunate, their characters are rarely transcribed so concisely, so methodically. My line of sight travels from the jagged headlands to the sawtoothed rocks below. How many people have jumped from here? I try to imagine them now, a foolish game; ersatz faces to pair with a thousand names.

Entry Two: Identity is housed in “non-places.”

Say what you will about airport lounges, I rather like them. Their sterility, the ambient humming of overhead lights. Overpriced drinks locked behind glass that is muddied by strange hands. Gum-strewn carpet sticking underfoot. Nobody knows me here. I am free to do as I please. I can leaf through magazines on home-renovation, wolf down processed crap, spend hours cycling through mind-numbing tweets. I look around. The people sitting beside me know nothing about me, and I know nothing about them. Strange.

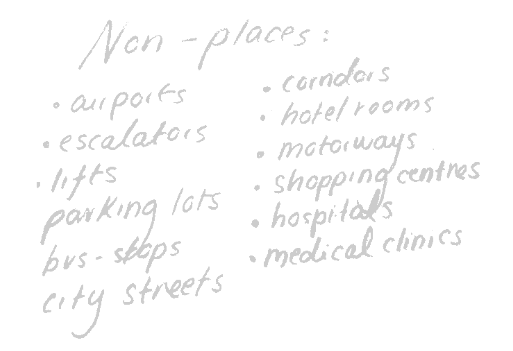

Marc Augé describes settings such as these as “non-places,” transient spaces that humans only inhabit for brief periods of time, rendering them insignificant by anthropological definition. I have included a list of examples below:

I think of all those times I have boarded trains too-late, accidentally brushing past strangers in a moment of frenzied panic, apologising in a manner similar to Joseph Baguenault: “‘Sorry,’ said he, and ‘Sorry.’ said they.” The exchange, of course, is meaningless. Here, Christina Stead employs repetitive, clipped dialogue to reinforce this notion, and both characters remain nameless, reduced to their respective pronouns. The passage, I think, expertly captures Joseph in a moment of total alienation. It is indicative of a deeper preoccupation amongst Modernist writers such as Stead, who began to see metropolitan “non-places” as potential agitators for the erosion of individuality; a reflection of the social poverty of post-industrial life.

Towards the Seven Poor Men of Sydney’s end, Catherine Baguenault checks herself into a psychiatric facility in the wake of her brother’s suicide. In doing so, Stead seemingly subverts the apathetic connotation of a “non-place,” with Catherine finding sanctity in the strangeness of the setting and her surrounding peers:

“I can only rest where other people are allowed to be queer…Everyone in the asylum pities the insanity of others.”

Catherine then begins to teach design within the asylum, and comes to derive individual meaning and purpose from it. A “non-place,” then, may be thought of as a facilitator of reflection; it creates internal space for dialogue and contemplation, for spiritual gain and the pursuit of personal interest.

Saturday, 7:23 am. I look around the airport lounge and sip from my five dollar bottle of Diet Coke, relishishing my newfound anonymity. I could be anyone here, I say to myself.

Entry Three: Identity is housed within the body.

There is an art to looking into mirrors; it is an extremely subtle undertaking. If I look too long, I am self-absorbed, narcissistic. I apply makeup or adjust my hair, and a gnawing thought begins to form somewhere at the base of my skull, knocking for some safe entry. I am not doing this for myself, but for someone else entirely. Looking back at my reflection, I am reminded of Atwood’s ‘The Robber Bride,’ of the performativity of it all: “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

The body has become a recurring metaphor in our privatised obsession with the search for identity. Think Susan Sontag’s ‘Illness as Metaphor,’ or Elaine Scarry’s ‘The Body in Pain.’ Fiona Wright touches upon similar subject matter in her essay, ‘To Run Away from Home.’ She says, “...the body and the home [being] linked is nothing new, of course…it is the thing that carries, or houses, our rational, remarkable minds —it is the home, that is, for who we are.” (6). Perhaps some ontological truth might be sought here then.

Several problems arise in applying this line of thought to the question of locating “agency,” however. If the subject is defined by their body — a malleable, transient thing — then the semantic meaning ascribed upon it is just as fluid. In the case of women too, who are vested with some agency but continuously subject to objectification, the body becomes a vessel onto which the concerns of the zeitgeist are projected as well as our own.

Wright’s essay suggests that an innate desire for self-improvement is born from this instability, a need to metaphorically “renovate” the body in a fashion similar to remodelling homes: “Transformation, desire and fantasy are also at the heart of the way we talk about changing our bodies, about dieting and fitness, renovating our physical appearances.”

A woman’s body is at war with itself then, powerfully impelled to change by the constricting impetus of societal conformity. We are told too many differentiating accounts of what is expected of us, how we should behave, what responsibilities we must undertake, and so on. As a result, we become estranged from our bodies and consequently, ourselves.

I look into the mirror once more. If I lean further forward and look dangerously close, I might find some kernel of authenticity reflected in my eye, my nose, my mouth. I might be able to say with conviction that that is who I am, that is me.

In her novel Seven Poor Men of Sydney, Christina Stead critically engages with such questions regarding female identity politics through her characterisation of Catherine Baguenault. In one such instance, she presents her brother Michael with two portraits of herself painted by two different men. The first depicts her as a “worn, crazy, young gypsy,” and the other as “an emaciated naked woman lying dead on the quays.” (36). There is a disturbing psychoanalytic transference that Stead denotes here. The paintings become a physical manifestation of the artists’ own subconscious hostilities towards Catherine, subjecting her body to punishment as a response to her desire to live beyond the constraints of societal convention and domestic confinement as a “vagabond queen” (132). Michael’s response only serves to expound this objectification further, with his misconstrual of the art perceived as Catherine merely navel-gazing, he asserts: “Her vanity was intense.” (36). Whilst Stead herself may not have identified with the label of feminism, her writing was fundamentally progressive and raises important concerns surrounding women’s lack of bodily autonomy under patriarchal directive.

Nearly one-hundred years on I am sitting at my desk reading Wright’s essay — a far more personal and confessional account that reads as dissimilar from Stead’s structurally, but responds to much the same ontological anxieties. Anecdotally, she describes the inherent disconnect she felt between herself and her body when she first began to suffer from anorexia: “Whatever my body had become, I no longer knew it. It was no longer safe, no longer forgettable, no longer my home.” (9).

For Wright, the monotonous routine of caloric restriction, of obsessing over the minutiae of dieting became a means of reclamation and control over her own body; something she felt no longer belonged to her. Writing, I suppose, may serve a similarly cathartic process. Within the feminist canon, literature has become a source of potential power and escapism for women to revalorise and reinstate their identities.

Fiction in particular has allowed for the destabilisation and radical subversion of self-limiting socio-political expectations. Women have found new ways to clearly inhabit space beyond the confines of the real world — though limited to paper. There is a typical literary form that critics and readers alike have begun to associate with this movement, too. I wonder what first springs to mind for others. For me, I think of a few things in particular:

These are all reflections of a deliberate stylistic shift towards the linguistic use of the self-referential ‘I’, the signifier of identity, of subjective truth. Wright’s essay is just one of many texts that reflect a broader cultural progression, one that seeks to assert female identity through the process of signification.

I sit cross-legged before the mirror yet again. What do I see? I see a face. Is it me, or some Other? Am I confusing myself with my mother? Who am I? I look around desperately, searching for someone to ratify this image, but I am all alone. A kind of hollowness blooms within my chest — manque d'être — a lack of being. Jacques Lacan’s damned “Mirror Stage.” Dylan Evans describes it as such:

“The baby sees its own image as whole [...], and the synthesis of this image produces a sense of contrast with the uncoordination of the body, which is experienced as a fragmented body; this contrast is first felt by the infant as a rivalry with its own image, because the wholeness of the image threatens the subject with fragmentation, and the mirror stage thereby gives rise to an aggressive tension between the subject and the image [...]” (Evans 2006).

At the risk of infantilising myself, I will admit that I feel as though I am still trapped within this psychoanalytic stage. I wonder if other women feel this too, if it is perhaps the primary reason why some of us are driven to write, to contribute to a tangible literary body; something that is fixed, something we can control and manipulate, something so unlike our own fleshy bodies.

I suppose what I am trying to get at is that there is something to be said for picking up a book and resonating with its subjects, fictional or otherwise. Catherine Baguenault, Fiona Wright; they are just two of the many individuals present in writing that reflect a greater collective of dissociative women operating under patriarchal institutions. As readers, there is some solace to be found here, we are offered a collective identity within this locus of writing, in its publicising of shared personal experiences.

In one of his many seminars, Lacan famously asserted that “all sorts of things in this world behave like mirrors.” I like to think of the body of feminist literature this way, as a mirror much bigger than the one that sits in the corner of my room, one that collates and reflects the experiences of other women, one so large and sprawling it cannot be measured. I stare into it, and the eyes of other women stare back. I see myself reflected in them.

Perhaps you may disagree with me and say that a collective identity is not the answer, it is simply too anaphorous, its direction too vague. I should think, however, given the issues touched upon in this entry, the reduction of female agency to a collective “we” is a tentative step in the right direction; it is making a virtue out of necessity.